Benner From Novice To Expert Pdf Creator

Benner's Stages of Clinical Competence In the acquisition and development of a skill. Advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. Stage 1: Novice.

•, RN, DNSc and •, MD • The School of Nursing, University of California, San Francisco, San Francisco, Calif (KD), and the Department of Anesthesiology, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY (CWB-B). The mediocre teacher tells. The good teacher explains.

The superior teacher demonstrates. The great teacher inspires. William Arthur Ward Many of us can relate to the story that Jon Carroll, a columnist for the San Francisco Chronicle, tells about his first public singing recital. He had taken a series of singing lessons and then found himself standing on a stage about to sing his first solo in front of a large audience. It took him 4 attempts to find the opening note while he also battled an uncontrollable head bob. Scanning the audience’s faces while he was singing, Carroll said he had the “unshakable perception that cyanide gas had been released in the room and that the face of every person... Was set in the final rictus of death.” The conclusion of the song was followed by polite applause (the same sort of applause, he wrote, that might occur at the end of a particularly painful 2-hour kettledrum solo).

But, to his surprise, his singing teacher walked over to him with tears running down her face and put her arm around him, saying proudly to the audience, “I just want to say that when this man came to me...he couldn’t even sing ‘Happy Birthday.’” The audience applauded wildly. Carroll was stunned at the teacher’s remarks and the audience’s reaction. Clearly, this was more than a teacher. She was a mentor. She inspired.

The Need for Nurse Mentors The nursing profession is in the midst of its longest and most severe shortage. The current shortage has been different from those in past years because of a continuous decline in nursing school enrollments. Causes of this decline include the opening of traditionally male-dominated professions to women, inadequate salary increases in nursing, and nurses speaking out vigorously about their dissatisfaction with the hospital work environment of the 1990s.

While fewer people have been seeking nursing careers, the demand for nurses has never been greater (with a projected need for 1 million more nurses by 2010). The aging of the baby boomers has created a population growth of elderly or soon-to-be-elderly patients, and advances in healthcare (particularly in our critical care specialty) have led to increasingly complex care. It appears, however, that the worst of the shortage may now be over, perhaps fueled by a depressed job market and a shortage of places for professional employment.

The American Association of Colleges of Nursing reported that nursing school enrollments had risen more than 16% in 2003 compared with the previous year. In addition to experiencing an influx of new applicants, nursing schools have adapted their curricula to incorporate accelerated programs and programs for people with baccalaureate degrees in other professions who wish to return to school to study nursing. Although these programs help produce more nurses quickly, they decrease the time devoted to gaining clinical experience. The influx of a substantial number of new nurses into the profession, many of whom may be relatively uninformed about the realities of today’s healthcare system, and the growth of accelerated programs present the next challenge for the critical care team in terms of assimilating these nurses into practice.

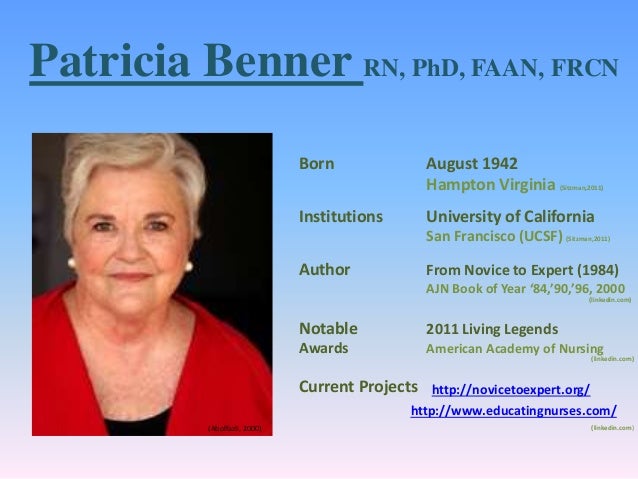

From Novice to Expert In her landmark work From Novice to Expert: Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice, Dr Patricia Benner introduced the concept that expert nurses develop skills and understanding of patient care over time through a sound educational base as well as a multitude of experiences. Saints Row 4 Main Menu Theme Скачать here. She proposed that one could gain knowledge and skills (“knowing how”) without ever learning the theory (“knowing that”). Her premise is that the development of knowledge in applied disciplines such as medicine and nursing is composed of the extension of practical knowledge (know how) through research and the characterization and understanding of the “know how” of clinical experience. In short, experience is a prerequisite for becoming an expert.

Until publication of Benner’s research, which focused on critical care nurses, this characterization of the learning process had gone largely undefined. What Does an Expert Nurse Look Like in the Clinical Setting? Benner used the model originally proposed by Dreyfus and described nurses as passing through 5 levels of development: novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient, and expert. Each step builds on the previous one as abstract principles are refined and expanded by experience and the learner gains clinical expertise. Instead of seeing patient care as bits of unrelated information and a series of tasks, the expert is able to integrate various aspects of patient care into a meaningful whole. For example, to the novice focusing on mastering the technical aspects of care, an unstable, critically ill postoperative cardiac surgery patient is an urgent to-do list. The vital signs must be noted every 15 minutes, the cardiac rhythm assessed, intravenous drips titrated to keep the blood pressure within a certain range, the lungs auscultated, chest tubes checked routinely, and intake and output recorded.

An expert nurse caring for the same patient would complete the same tasks but not be caught up in the technical details. The expert integrates knowledge of cardiovascular physiology and pathophysiology to assess symptoms and guide patient care; for example, the skin is a little cooler than it should be, the patient is harder to arouse than he was an hour ago, the pulse oximeter shows a decrease in arterial oxygen saturation, and the cardiac monitor shows an irregular heart rhythm. The expert integrates such information and determines that the irregularity is new onset atrial fibrillation and that the cardiac output has probably dropped as a result. The expert knows to watch for emboli, adjust intravenous medications to maintain blood pressure, monitor for other signs and symptoms of reduced cardiac output, and notify the physician about the patient’s change in status. The expert has gone beyond the tasks to read and respond to the whole picture. A potential catastrophe (“failure to rescue” in the lingo of patient safety) is averted.

From Expert to Preceptor The understanding of what makes an expert nurse has been integral in developing preceptor roles in the intensive care unit (ICU) that help impart this experiential knowledge to nurses new to critical care. The critical care clinician (physician or nurse) makes hundreds of complex decisions each day.

It is impossible to teach the myriad circumstances and conditions that a clinician might face daily in the classroom setting or even in a clinical simulation. The clinical expert has a solid technical foundation and the critical thinking skills to adapt to the unique condition of each patient. Preceptors help new nurses deal with the uncertainty of the clinical setting that is inherent to gaining proficiency. Ultimately, both nursing and medicine are taught in an apprenticeship system, and the role of the “guide at the side” is critical to moving from novice to expert.

Imparting knowledge gained by years of experience can be difficult and frustrating for the preceptor and novice alike. The preceptor has learned perceptual distinctions that may be difficult for the novice to understand or the preceptor to teach. In training experts to be preceptors, facilitators will often use methods that help bring the preceptor back in time to the novice stage. For example, at one local hospital, the instructor responsible for teaching nurses how to be good clinical preceptors brings a musical recorder, an instrument similar to a flute, for each nurse in the class. After giving the class a series of instructions on how to play the recorder, each new clinical preceptor is asked to stand in front of the group and play. This one simple lesson reminds future preceptors what it is like to be a novice and helps them guide new staff nurses skillfully and with empathy. Inexperienced ICU nurses must deal with a wide variety of complex situations and conditions, many of which they are seeing for the first time.

They may feel unsure and vulnerable to being revealed as frauds. Preceptors have to intervene in this potentially lethal situation and give new nurses confidence while carefully monitoring their actions.

Being a learner in the challenging environment of an ICU can be difficult, and novice nurses may feel an incredible sense of failure or shame when they make a mistake. Mentors Wanted The anticipated influx of new nurses will most likely put demands on current clinical nurse experts and require that they step up into a mentor role for this next generation of nurses. Mentorship has its earliest roots in Homer’s Odyssey written almost 3000 years ago. As the story goes, the goddess Athena assumed the role of a nobleman named Mentor in order to teach Telemachus, Odysseus’s son, and to guide him through life’s challenges. Robert Fitzgerald correctly refers to Athena’s cognomen in the first book of the Odyssey as “Mentes.” We need talented mentors to guide the next generation of nurses. If the only nurse mentors who apply for the job are those who are long on experience but short on knowledge and skill, we will scare off the next generation!

The concept of a mentor is familiar in the world of business, but more foreign to nursing. Mentors do more than teach skills; they facilitate new learning experiences, help new nurses make career decisions, and introduce them to networks of colleagues who can provide new professional challenges and opportunities. Mentors are interactive sounding boards who help others make decisions. We like the 5 core competencies of leaders and mentors developed for the Robert Wood Johnson Nurse Fellows Program. The first competency is self-knowledge—the ability to understand and develop yourself in the context of organizational challenges, interpersonal demands, and individual motivation. Mentors are aware of their individual leadership strengths and have the ability to understand how others see them.

Mentors are also aware of their personal learning styles and are able to work with the different styles of other people. The second competency is strategic vision—the ability to connect broad social, economic, and political changes to the strategic direction of institutions and organizations. With strategic vision, mentors have the ability to identify key trends in the external environment (eg, reimbursement policies for hospitals, changing roles for men and women, changing patient demographics) and understand the broader impact of the environment on healthcare. With this competency, leaders are able to focus on goals and advise wisely.

The third competency is risk-taking and creativity—mentors have the ability to be successful by moving outside the traditional and patterned ways of success. They are able to identify creative responses to organizational challenges and can tolerate ambiguity and chaos. The mentor is one who develops and sustains creativity and entrepreneurship, encouraging others to take risks and turn mistakes into opportunities for growth. The fourth competency is interpersonal and communication effectiveness.

Great mentors have the ability to nurture a partnership that is mutual and equal, not patriarchal or matriarchal. This skill set requires that mentors be able to give the people they guide a feeling of being included and involved in the relationship. Mentors are great communicators and also great active listeners. They avoid power struggles and dependent relationships and are respectful of the people they guide. They nurture team performance and accountability and give the lifelong gift of confidence.

The fifth competency is inspiration. Mentors are ultimately change-agents who create personal as well as organizational changes. Change is always difficult, and mentors understand and address resistance to change and build teams that can move from planning to action. Mentors encourage change by making others feel hopeful and optimistic about the future. They are able to set a positive and constructive tone and are committed to facilitating growth and career opportunities for others. The Future of Nursing Our opening premise was that we needed to prepare for the challenge of the influx of new nurses at hospitals around the country.

Developing preceptor and mentorship programs within our organizations is one effective way to integrate and support the nurses of tomorrow. We need to create these programs if they don’t exist and encourage our colleagues and administrators to support them and participate in them. The acute need for mentors is not a problem that can be solved by nursing alone.

Other disciplines can assist with mentoring, and administrators can incorporate incentives for preceptors and mentors, such as salary compensation and career ladder rewards. With the current influx of new nurses into the profession, we have an opportunity to shape the healthcare system of tomorrow. We can create a system that values talent and generosity of spirit and that rewards professional commitment. Clinical preceptors and career mentors are key to the growth of the nursing profession.

Introduction Efforts to improve healthcare quality and safety have focused on developing technology designed to improve diagnostic accuracy, provide easier and more rapid access to patient information and more complete medical records (). Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) are one prominent example of this type of technology. However, development and implementation of these tools to assist health care providers in their clinical practice has lagged especially in nursing. A significant obstacle has been the identification of nursing information and knowledge. Differential use and manipulation of nursing information by nurses with differing nursing practice levels compound this obstacle. Thus, not all nurses recognize the same nursing data or information as pertinent to their clinical practice and knowledge. The aim of this paper is to explore how Novice-to-Expert Nursing Practice framework can illuminate the challenges of and opportunities for planning and implementing a clinical decision support system in nursing practice.

Furthermore, we will provide a descriptive overview of clinical decision support systems and discuss the concepts of both nursing knowledge and roles as they pertain to the use of such systems in nursing practice. Information technology in nursing practice: risk and reward There has been an increasing trend over the past decade in the use of information technology (IT) in clinical settings; however, there has also been mounting evidence that many of these systems are failing ().

Actual costs associated with these system failures are difficult to determine and have rarely been reported. One recommendation to determine costs is to calculate differences in intended and observed effects of implementation processes ().

For example, the process of automation could be equated with the rising costs associated with increased clerical workload. In the nursing process, the elimination of existing processes or duplication could represent decreased costs. Several reasons can lead to failure or poor adoption of information technology in a health care setting. Information systems failures have been attributed to ineffective ongoing communication, competency of users, intuitiveness of the system design, system acceptance and change management procedures (, ). According to a framework developed by, failure to adopt IT systems in health care settings can be linked to a combination of several factors including attributes of the individual end users (e.g.

Computer anxiety, motivation), attributes of the technology (e.g. Usability, performance) and attributes of the clinical tasks and processes that the IT application introduces or affects (e.g. Task complexity). Failure of IT solutions is often also attributed to lack of communication between end users and designers ().

Clinical decision support systems Clinical decision support systems (CDSS) are information systems that model and provide support for human decision-making processes in clinical situations (). CDSS use technology to support clinical decision making by interfacing evidenced-based clinical knowledge at the point of care with real-time clinical data at significant clinical decision points (,, ). CDSS enable clinician-computer interactions that move away from traditional data gathering roles to support clinicians as knowledge workers and information users (). Four classes of CDSS have been described in patient care decision making: systems that (1) use alerts to respond to clinical data, (2) respond to decisions to alter care by critiquing decisions, (3) suggest interventions at the request of a care providers, or (4) conduct retrospective quality assurance reviews. Many systems have been developed for a myriad of clinical issues in acute care settings including diagnosis of chest pain, ventilator management and to improve adherence to recognized HIV treatment guidelines (,,, ); however these are rarely nursing specific. Nursing-specific decision support systems include nursing diagnosis systems such as the Computer Aided Nursing Diagnosis and Intervention (CANDI) system (); care planning systems such as the Urological Nursing Information System (); symptom management systems such as the Cancer Pain Decision Support system () and nursing education systems such as the Creighton Online Multiple Modular Expert System (COMMES; ).

Expert systems have also been proposed for the reduction of nursing care errors through surveillance systems for nursing administrators to detect acute increases in staffing demands (). CDSS using an active interaction model, such as generating clinical alerts or reminders with clinician data entry, have been shown to be the most effective in improving clinical practice (). The idea of employing CDSS for nursing is based on the belief that nurses are ‘knowledge workers’ (, ). Knowledge workers work within knowledge intensive environments and use information processing and specialized knowledge to evaluate decision-making processes and outcomes (). As knowledge workers nurses have four roles: data gatherers, information users, knowledge users and knowledge builders.

These roles involve clinical data storage (data gatherer), interpreting clinical data into information (information user), connecting clinical data to domain knowledge (knowledge user) and recognizing clinical data patterns across patients (knowledge builder) (). CDSS can support nurses in these various roles. CDSS can assist with data capture and storage for the data user; display and summarize data for the information user; link domain knowledge to clinical data for the knowledge user; and aggregate data to generate clinical patterns across patients for the knowledge builder ().

First generation CDSS that assisted in clinical decision making were developed in the 1950s. They were mainly based on methods using decision trees or truth tables; CDSS using statistical probabilities appeared later and were followed by expert systems (, ). Multiple methods of reasoning have been used in the design of CDSS but all are contingent on a well-developed knowledge base (,, ). Fragmented, incomplete or unreliable clinical data sets will hinder the recognition of patterns and associated outcomes. Quality, accuracy and design will ultimately affect the system’s overall performance and its clinical utility. Identifying what information is pertinent for nursing remains a challenge for the development of clinical decision support systems.

Therefore, CDSS that support the data gatherer role can also contribute to the creation of reliable and valid clinical data sets (). Nursing practices: Benner’s framework for nursing practice One of the issues in planning and implementing clinical decision support systems for nurses is the wide variation in knowledge, experience or practice levels. However, the issue of experience level is rarely addressed in most CDSS design with the exception of CDSS that specifically target medical or nursing education. In her seminal work, proposed five levels of practice for nursing (novice, advanced beginner, competent, proficient and expert).

Later work described four levels of nursing practice () that include: advanced beginner/novice, competent, proficient and expert. Experiential learning was a central component of Benner et al.’s adaptation of the Dreyfus Model of Skill Acquisition to clinical nursing practice (). These levels of clinical practice mark four major shifts in clinical practice through progression of the different levels () and are useful for understanding how nurses use and generate data and information as their practice evolves over time (). Novice/advanced beginners Novice and advanced beginners (up to 6 months of clinical experience) focus on the immediate needs for action for a clinical situation based on rules, protocols and practice structures such as flow sheets or structured documentation ().

The focus of their practice is the organization and prioritization of their tasks. Advanced beginners attend to the current clinical situation rather than potential status changes and the potential influence of nursing interventions (). Novice or advanced beginner nurses have also been the target of recent CDSS research initiatives. Described a theoretical model for novice clinical decision making that was developed as part of their efforts to design a point-of-care CDSS for novice nurses (N-CODES). The model provided by corresponds with the narrative descriptions in and.

The advanced beginner’s desire for organizing and prioritizing the tasks to be completed can make them a receptive audience for CDSS. However, the decision support provided from CDSS may not be what the advanced beginner needs. CDSS could be beneficial in providing guidance for action for unfamiliar situations for advanced beginners but might not help them in differentiating the clinical situation from textbook examples (). Competent Competent nurses focus on organization of tasks and care plans. The competent nurse begins to recognize the limitations of protocols and practice structures; however, recognition of and adaptation to changing situations is affected by a preference for pre-set goals and plans and a sense of mastery when a routine is achieved.

The competent nurse may find that CDSS that provide care plans or care trajectories are helpful in setting goals and plans for patient care. However, competent nurses may be more skeptical about the suggestions of a CDSS as a result of an increased recognition that practice structures or directives may not be sufficient. Note that competent nurse performance as described by goal setting and standard care plans is what is institutionally rewarded and encouraged as standard practice.

An institutional focus on this level of practice could drive CDSS design and create a CDSS that again promotes this level of practice to the detriment of further professional practice growth and patient care. Proficient Proficient nurses are better able to see changing relevance in clinical situations (). This ability to read the clinical situation quicker allows the proficient nurse to establish situation-specific priorities (). CDSS may not be able to extend the clinical practice of a proficient nurse to an expert practice level. However, the knowledge and experience of proficient and expert nurses can be used in developing CDSS. Proficient nurses should be recruited for both CDSS planning and implementation teams.

Bringing advanced beginner nurses and competent nurses to the proficiency practice level rather than expert level may be a realistic goal of the CDSS. Expert Expert nursing practice is developed to a greater extent than the proficient nurse’s practice. The expert nurse immediately grasps familiar situations and recognizes when he or she does not have a good grasp of a situation (). ‘Experts are open to the clinical situation in that their grasp is not determined, formed, by expectations, sets and formal knowledge in general, although these aspects are clearly in the background’ (, p. Note that the expert nurses can only vaguely describe their clinical knowledge. The difficulty in articulating or formalizing expert practice will also make it difficult to capture this type of clinical knowledge with a CDSS. Additionally, given the nature of expert practice, it is difficult to speculate how a CDSS might enhance an expert nurse’s practice.

More research is needed to determine what can be translated from expert nursing practice to CDSS to enhance the practice of other nurses., p. 279) suggest that practice narratives are needed for ‘describing the knowledge embedded in the particular, historical, clinical relationship’. Key issues The design of CDSS for nurses needs to account for nursing data, information and knowledge (). Typically nursing CDSS have been designed for information management purposes rather than knowledge generation.

Given the difficulty in identifying pertinent nursing information and describing nursing knowledge, nurses need to be actively involved in the design, planning, implementation and evaluation phases of nursing CDSS. Although this involvement seems obvious, past development and planning of CDSS for nurses has not always involved nurses (). Recommendations for nursing managers and administrators are included in. User participation User participation in the design and development of information systems such as decision support systems increases the likelihood of successful implementation and utilization of these systems (,, ).

Involvement of end users in the design and implementation of a system is likely to result in increased user satisfaction (, ), and an increase in the perception of usefulness of the application by the end user (, ). On the other hand, lack of communication between end users and designers is often linked to failure of information technology implementations () and misuse of override functions. Thus, it becomes critical for the success of a clinical decision support system that targets or involves nurses as end users to include them in the conceptual phase of the system design. As stated earlier, end-user involvement in the system design is critical to the overall successful implementation of an information system.

In this context, nurses need to be actively involved in the system planning and implementation phases and lead the customization of interfaces based on the different roles they may assume as knowledge workers and end users, namely data gatherers, information users, knowledge users and knowledge builders. Human computer interaction Carter noted that several human-computer interaction problems can plague the development of CDSS (1999). These issues include: clinical importance of the CDSS domain; clinician workflow; scope of CDSS (single vs. Multiple problem use) and organizational readiness (). For clinicians to adopt a new CDSS, they must feel that it addresses a particular and important concern for clinical practice.

For example, a system that addresses prostate cancer treatment, an area which contains substantial uncertainty, could be more useful to clinicians than a system that addresses paediatric bladder training protocols, an area in which standards are well documented and the risk to patients is low. Likewise, a CDSS must fit within the workflow of the clinician. A system that requires a critical care nurse to leave the bedside for prolonged periods of time is not likely to be adopted. Conversely, systems that are designed to integrate with nurse clinicians established time management practices are more likely to be adopted. For example, clinical reminders for discharge could be delivered ‘just in time’ during the discharge process.

Information technology affects work processes, communications and the point of care (). Pointed out that often workflow and CDSS scope problems magnify each other. If a CDSS is designed to provide guidance for a narrow clinical issue, the likelihood of clinicians to interrupt their workflow to use the CDSS diminishes; whereas a system that has a broader scope is more likely to be consulted and integrated into practice. Lastly, organizational issues are rarely examined when developing a CDSS.

Organizational issues include both administrative support (persons and resources) of the project in addition to the identification of ‘power users’ and ‘unit champions’ who will help facilitate the CDSS use in practice (). Encoding challenges ‘There must be acknowledgement that not all nursing knowledge is amenable to computerization. Given nursing’s holistic focus, the profession is not able to codify or standardize all of its data, information, and knowledge’ (, p. This is echoed in work which suggests nursing work that is easily captured by the scientific reasoning process will be easily captured by computerized systems.

Although it seems straightforward that perhaps nursing knowledge which is readily coded will be the nursing knowledge that is available for use in nursing decision support systems, there are remaining issues with integrating this knowledge base as well. In their review of nursing languages, note that none of the existing nursing vocabularies meet all of the Computer-based Patient Record Institute’s (CPRI) criteria for classification systems for implementation in an EHR. Conclusion Expert systems designed for the nursing profession have not gained wide use in spite of overall positive attitudes of nurses towards such decision support tools documented in the literature. In a study by, physicians and nurses rated access to patient data and clinical alerts highly in CDSS. Neither group felt that computerized decision support decreased their decision-making power. The study findings indicated that nurses embraced expert systems as useful tools as much as their physician counterparts.

Also found enthusiasm among nurses and initial results of the use of a nursing expert system were positive but subsequent analysis identified significant limitations of the system to mimic the consultation process of advanced practice nurses. Such challenges, associated with the design and implementation of expert systems for nursing, have been discussed in this paper. It becomes evident that computerizing nursing knowledge is not an effortless process. However, the holistic focus of nursing should not be viewed as an impediment to the diffusion of expert systems for the nursing profession. In spite of this and additional challenges highlighted in this paper, nursing expert systems can improve the overall quality of care when designed for the appropriate end-user group and based on a knowledge base reflecting nursing expertise. As is the case with all expert systems, they should be viewed as useful tools for a specific target group and not products that replace the decision maker, nor aim to simultaneously aid all professional groups and all levels of knowledge workers. Organizational support for both nurses and nursing practice is a critical component for successful implementation of clinical decision support systems.

We recommend further development of nursing CDSS with input from nurses. Such development should address the differing information and knowledge needs of various practice levels.

Additionally, nurses chosen to participate in CDSS implementation teams should possess the same attributes as skilled nursing preceptors, namely, domain expertise and an understanding of the different needs of nurses with various practice levels. Continuing research in encoding nursing information and knowledge such as nursing language development will further support the development of CDSS for nursing.

• Abbott PA, Zytkowski ME. Supporting clinical decision making. In: Englebardt SP, Nelson R, editors. Health Care Informatics: An Interdisciplinary Approach. Mosby; St Louis, MO: 2002.

• Alexander GL, Rantz MJ, Flesner M, Diekemper M, Siem C. Clinical information systems in nursing homes: an evaluation of initial implementation strategies. Computers, Informatics, Nursing.

2007; 25(4):189–197. [] • Ammenwerth E, Iller C, Mahler C. IT-adoption and the interaction of task, technology and individuals: a fit framework and a case study. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making. 2006; 6(3) Available at:, accessed on 6 November 2007. [] [] • Barki H, Hartwick J. Measuring user participation, user involvement and user attitude.

MIS Quarterly. 1994; 18:59–82. From Novice to Expert Excellence and Power in Clinical Nursing Practice. Addison-Wesley; Menlo Park, CA: 1984. • Benner P, Tanner CA, Chesla CA.

From beginner to expert: gaining a differentiated clinical world in critical care nursing. Advances in Nursing Science. 1992; 14:13–28. [] • Benner P, Sheets V, Uris P, Malloch K, Schwed K, Jamison D. Individual, practice and system causes of errors in nursing. Journal of Nursing Administration.

2002; 32:509–523. [] • Bussen WS, Myers MD. Executive Information Systems Failure: A New Zealand Case Study. Information Systems Management Research Concentration, QUT; Brisbane, Australia: 1997.

Design and implementation issues. In: Berner ES, editor. Clinical Decision Support Systems Theory and Practice. Springer; New York, NY: 1999.

• Chang BL, Roth K, Gonzales E, Caswell D, Distefano J. CANDI: a knowledge-based system for nursing diagnosis.

Computers in Nursing. 1988; 6:13–21. [] • Courtney KL, Demiris G, Alexander GL. Information technology: changing nursing processes at the point-of-care.

Nursing Administration Quarterly. 2005; 29:315–322.

[] • Demiris G. Examining health care providers’ participation in telemedicine system design and implementation. AMIA Annual Symposium Proceedings. 2006; 906 [] [] • Despont-Gros C, Mueller H, Lovis C. Evaluating user interactions with clinical information systems: a model based on human-computer interaction models.

Journal of Biomedical Informatics. 2005; 38:244–245. [] • East T, Heerman L, Bradshaw R, Lugo A, Sailors RM, Ershler L. Efficacy of Computerized Decision Support for Mechanical Ventilation: Results of a Prospective Multi-Center Randomized Trial. AMIA 2005 Fall Symposium; Washington, DC: 2005. [] [] • Foster ST, Franz CR. User involvement during information systems development: a comparison of analyst and user perceptions of system acceptance.

Journal of Engineering and Technology Management. 1999; 16:329–348. • Franz CR, Robey D. Organisational context, user involvement, and the usefulness of information systems. Decision Sciences.

1986; 17:329–356. • Garceau L, Jancura E, Kneiss J. Object oriented analysis and design: a new approach to systems development. Journal of Systems Management.

1993; 44:25–33. • Gardner RM, Lundsgaarde HP. Evaluation of user acceptance of a clinical expert system. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1994; 1:428–438.

[] [] • Garg AX, Adhikari NK, McDonald H, et al. Effects of computerized clinical decision support systems on practitioner performance and patient outcomes. Journal of the American Medical Association. 2005; 293:1223–1238.

[] • Graves JR, Corcoran S. The study of nursing informatics. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1989; 21:227–231. [] • Harris MR, Graves JR, Solbrig HR, Elkin PL, Chute CG. Embedded structures and representation of nursing knowledge. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association.

2000; 7:539–549. [] [] • Henry SB, Warren JJ, Lange L, Button P. A review of major nursing vocabularies and the extent to which they have the characteristics required for implementation in computer-based systems. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 1998; 5:321–328.

[] [] • Im EO, Chee W. Decision support computer program for cancer pain management. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing. 2003; 21:12–21.

[] • Kawamoto K, Houlihan CA, Balas EA, Lobach DF. Improving clinical practice using clinical decision support systems: a systematic review of trials to identify features critical to success. 2005; 330:765.

[] [] • Lappe JM, Dixon B, Lazure L, Nilsson P, Thielen J, Norris J. Nursing education application of a computerized nursing expert system. Journal of Nursing Education. 1990; 29:244–248.

[] • Lorenzi NM, Riley RT. Managing change: an overview. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2000; 7:116–124. [] [] • Marques IR, Marin H.

A Model for a Web-based Nursing Decision Support System in Acute Myocardial Infarction. NI 2003 – 8th International Congress in Nursing Informatics; Rio de Janeiro, Brazil. Cherry Lisa Shaw Rar Extractor more. • McKeen JD, Guimaraes T, Wetherbe JC. The relationship between user participation and user satisfaction: an investigation of four contingency factors. MIS Quarterly.

1994; 18:427–451. • McKinley B, Moore FA, Sailors RM, et al. Computerized decision support for mechanical ventilation of trauma induced ARDS: results of a randomized clinical trial.

Journal of Trauma. 2001; 50:415–424. [] • Meyer KE, Sather-Levine B, Laurent-Bopp D, Gruenewald D, Nichol P, Kimmerle M.

The impact of clinical information systems research on the future of advanced practice nursing. Advanced Practice Nursing Quarterly. 1996; 2:58–64. [] • O’Neill ES, Dluhy NM, Chin E. Modelling novice clinical reasoning for a computerized decision support system. Journal of Advanced Nursing.

2005; 49:68–77. [] • Ozbolt JG. Knowledge-based systems for supporting clinical nursing decisions. In: Ball MJ, Hannah KJ, Jelger UG, Peterson H, editors.

Nursing Informatics: Where Caring and Technology Meet. Springer-Verlag; New York, NY: 1988. • Patterson ES, Nguyen AD, Halloran JP, Asch SM.

Human factors barriers to the effective use of ten HIV clinical reminders. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2004; 11:50–59. [] [] • Petrucci KE, Jacox A, McCormick K, et al.

Evaluating the appropriateness of a nurse expert system’s patient assessment. Computers in Nursing. 1992; 10:243–248. [] • Sage AP. Decision support systems. In: Salvendy G, editor.

Handbook of Human Factors. John Wiley & Son’s, Inc; New York, NY: 1997. • Sicotte C, Denis JL, Lehoux P.

The computer based patient record: a strategic issue in process innovation. Journal of Medical Systems. 1998; 22:431–443. [] • Sim I, Gorman P, Greenes RA, et al. Clinical decision support systems for the practice of evidence-based medicine.

Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association. 2001; 8:527–534. [] [] • Snyder-Halpern R. Assessing healthcare setting readiness for point of care computerized clinical decision support sysetm innovations.

Outcomes Management in Nursing Practice. 1999; 3:118–127. [] • Snyder-Halpern R, Corcoran-Perry S, Narayan S. Developing clinical practice environments supporting the knowledge work of nurses. CIN: Computers, Informatics, Nursing.

2001; 19:17–26. [] • Spooner SA. Mathematical foundations of decision support systems. In: Berner ES, editor. Clinical Decision Support Systems Theory and Practice. Springer; New York, NY: 1999. • Staggers N, Thompson C, Snyder-Halpern R.

History and trends in clinical information systems in the United States. Journal of Nursing Scholarship.

2001; 33:75–81. [] • Tanner CA, Benner P, Chesla CA, Gordon DE. The phenomenology of knowing the patient. Image: The Journal of Nursing Scholarship. 1993; 25:273–280. [] • Van Bemmel JH, Musen MA, Miller RA, Van der Maas AAF.

Methods for decision support. In: Van Bemmel JH, Musen MA, editors. Handbook of Medical Informatics. Springer; Bohn: 1997. • Van der Lei J, Talmon JL. Clinical decision support systems. In: Van Bemmel JH, Musen MA, editors.

Handbook of Medical Informatics. Springer; Bohn: 1997. • Woolery LK. Professional standards and ethical dilemmas in nursing information systems. Journal of Nursing Administration.

1990; 20:50–53.